My training in Latin American Cultural Studies shaped my research on the fraught politics, landscapes and visual cultures of modernity and their contemporary afterlives. My doctoral and postdoctoral research was motivated by a deep concern for the resurgence of the authoritarian right in Latin America and beyond -a preoccupation that stands to this day. I confronted this by tracing connections between developmentalism, landscape and dictatorship.

Spectacular Modernity

While living in Venezuela from 2005 until 2013, I was fully embedded in the complexities of widespread nostalgia for the “progress” of the 1950s military dictatorship and the political polarisation of the Chávez era, as well as the increasing precarity of state archives which hold the material memory of mid-twentieth century modernization. My monograph, Spectacular Modernity, published by Pittsburgh University Press, offered an unprecedented analysis of how military rule from 1948 till 1958 in Venezuela produced a dominant ideology of progress so meticulously crafted that to this day audacious Modernist art and architecture and dictatorship are simplistically conflated under the umbrella term ‘modernity’. For ten years the military state sought to construct an imaginary of a modern nation by sponsoring a boom in propaganda, urban development and infrastructure, the vestiges of which are now a vital part of the nation’s celebrated cultural heritage. Celebrations of this period have reached the extent that today it elicits nostalgic reminiscences of a bygone golden age among Venezuelans.

The thesis that modernity was rendered a spectacle makes an important contribution to understanding the political history of military statecraft through a cultural studies lens and to uncovering the aesthetic language of urban and architectural design, mass media and nascent consumer culture that amplified the sense of “progress”. This interdisciplinary approach engages political issues, while identify scopic regimes of viewing and visuality as the core tropes of this ruling ideology of modernity, designed to legitimize an undemocratic regime, neutralize its political opposition and incorporate the populace into the narrative and imaginary of progress.

From Modernist Mall to Political Prison

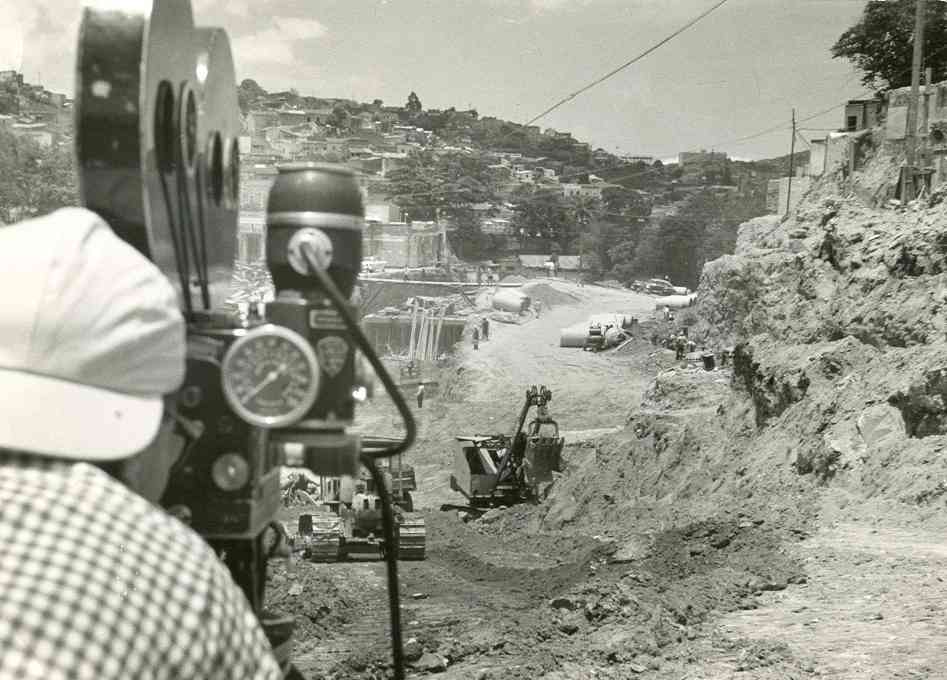

In collaboration with Celeste Olalquiaga, this research expanded to address the turbulent legacy of the 1950s modernist would-be mall, El Helicoide, partially constructed in Caracas and then abandoned as funds ran out. Its latter transformation into a temporary homeless shelter and police headquarters and jail (a function it continues to have today) enabled us to trace the afterlives of the mid-century aspiration for fast-paced petromodernity in Venezuela. Built between 1956 and 1961, El Helicoide would have been the largest and most state-of-the-art mall in the Americas, as its stellar appearances in MoMA’s 1961 Roads exhibition and on the front pages of major international magazines clearly attest. At a cost of $10 million (equivalent to $90 million today), the building was conceived as a gigantic showroom for the country’s emerging oil and mineral industries, as well as hub for commerce and entertainment. El Helicoide’s surrounding barrios, namely those of San Agustín del Sur, were always implicitly part and parcel of the project’s mission. One of several “cities within a city” (along with the Universidad Central de Venezuela and the Centro Simón Bolívar, among others) El Helicoide played a founding role in the urban planning of mid-century Caracas, which stigmatized poor communities as signs of “backwardness.” Not only did El Helicoide’s construction coincide with the broad-ranging, state-led projects created to demolish such ad hoc housing, the building itself was to cap a reforestation project that entailed razing the shantytowns installed on the site’s surrounding hills, a plan revisited several times during the 1960s and 1970s to no avail.

Spatial and Archival Legacies of Political Violence

This work ran parallel the project I began in 2011 when working at the Universidad Simón Bolívar and continued during my postdoctoral project at Universität Zürich, into the amnesia surrounding clandestine opposition and political oppression of left wing insurgents in the 1950s. Delving into personal archives of families of deceased activists, out-of-print memoirs and novels, documents of resistance written in sites of incarceration, I assembled an counter-archive of the official narrative of the 1950s that enabled a re-emergence of the memory politics forged in Venezuela’s return to democracy in the 1960s, as left-wing militants entered the ranks of cultural institutions.

This inquiry into how violence is forgotten also involved seeking traces of the entangled ecology of mud, water and traces of the architecture and violence of incarceration in the Orinoco Delta. By assembling documentary memories from poetry, memoir and film, I explored the ways the matter of water and mud has posed challenges to constructing and maintaining the cultural memory of Guasina, a former island prison located in the Orinoco’s remote riverways, that functioned as an infrahuman jail and forced labour camp for a short period during the military dictatorship of 1948-1958. Given that public awareness of the site is extremely limited, this research navigated the dislocated space-time of Guasina, thinking through the ways the Delta’s ecology is simultaneously the grounds of its material condition and the material cause of the former prison’s oblivion as it is cyclically inundated and exposed by the changing river flow.

Space as Witness of Contested Memories

During my postdoctoral work, I expanded this research project into the history of urban development during the regime of Rafael Trujillo (1936-62) in the Dominican Republic, the contentious present of memory politics and the cultural infrastructure of memory museums. Alongside several articles, I co-directed the research-led documentary Después de Trujillo (After Trujillo). Narrated by Dominicans, Después de Trujillo tells the story of the violent dictatorship of Rafael Trujillo through the marks it left on the landscape and in people’s memories. Myriad voices —from activists and torture victims, to historians and architects— guide this journey through monuments, memory gardens, and contemporary ruins. In the sites where past trauma lives on after Trujillo, Dominicans struggle to live with the legacy of violence, pondering whether built environments and natural landscapes attest to the experience of dictatorship or bury it in oblivion instead. From the cyclone that devastated Santo Domingo as Trujillo came to power, via the modern architecture erected to consolidate his regime, and through to the testimonies of resistance that led to his demise, the film blends interviews, archival materials, and new footage to pick through the ruins of dictatorship.

Research-led film enables me to weave fieldwork to public outreach, offering an enriched way to disseminate archival materials and testimonies beyond the limited reach of conventional books and articles, creating contact points between academic debates and public spheres. This feature-length film is based on footage gathered during fieldwork in the Dominican Republic in 2015, comprising site visits, interviews, and archives from the Archivo General de la Nación; the Museo Memorial de la Resistencia Dominicana; and the Centro León. The documentary was completed in November 2016 and premiered soon after in the Dominican Republic, with screenings at universities, cultural institutions, museums, and archives. Since then Después de Trujillo has been screened at universities in Canada, the US, and Switzerland.

Public Scholarship

Throughout this work, engaging with people whose lived experiences connect them to the places I was working with was of fundamental importance.

Writing and publishing in English means that scholarly work does not always feed back into communities with whose histories and landscapes I am thinking. This is another reason why research-led film and also collaborating with other projects, such as the BBC’s interactive documentary and investigative journalism on El Helicoide, its history and current use as a political prison, is one way to start bridging that gap.

Archivo Histórico de Miraflores.

Carnavales, 1954. Archivo Histórico de Miraflores

El Helicoide exhibited at The Museum of Modern Art show Roads, 1961. In the picture Ragnhild Goetz, Dirk Bornhorst’s wife. Archivo de Fotografía Urbana/Proyecto Helicoide.

El Helicoide occupied by “damnificados”, c. 1979.

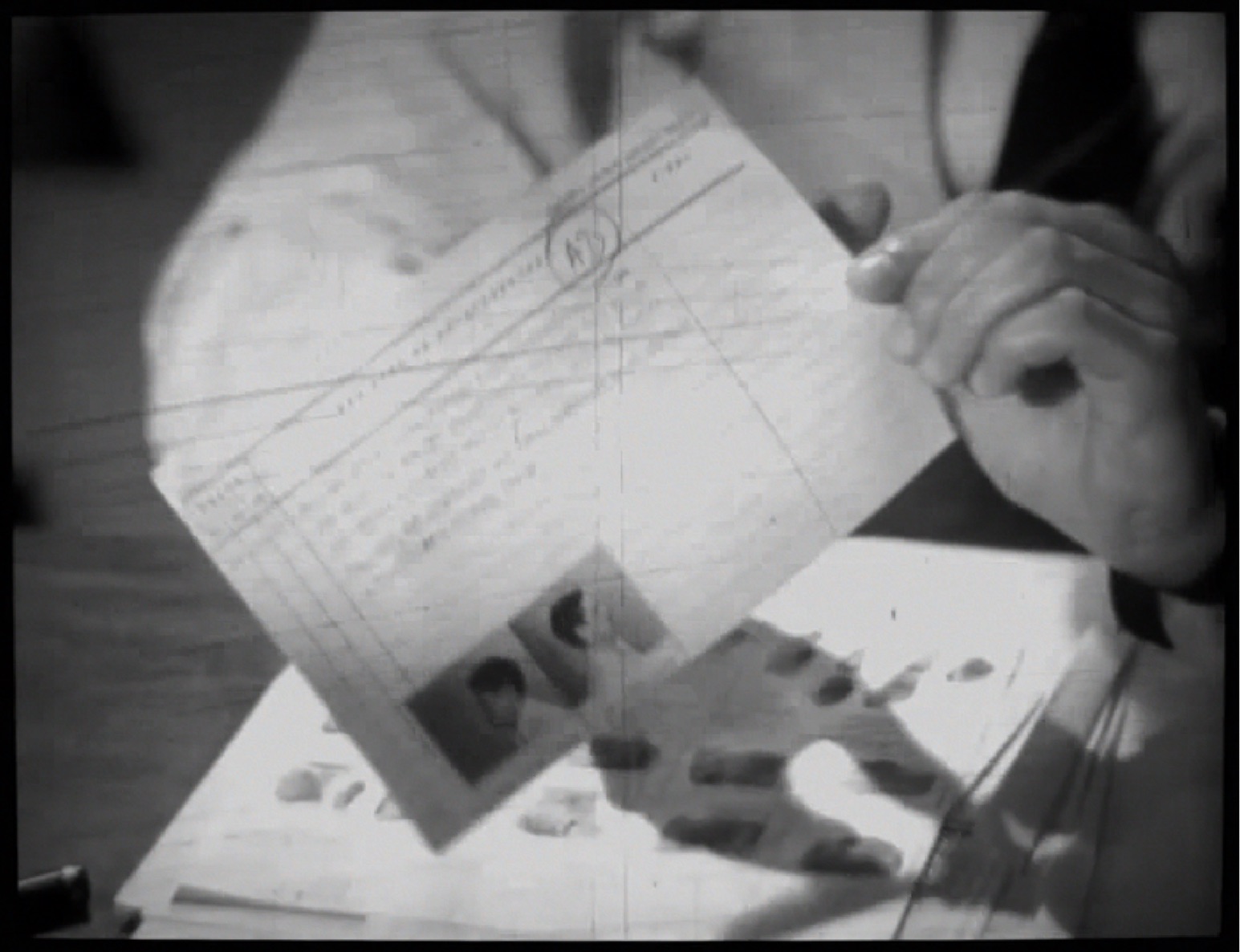

Still of the damaged film Se llamaba SN. Photo: Lisa Blackmore.

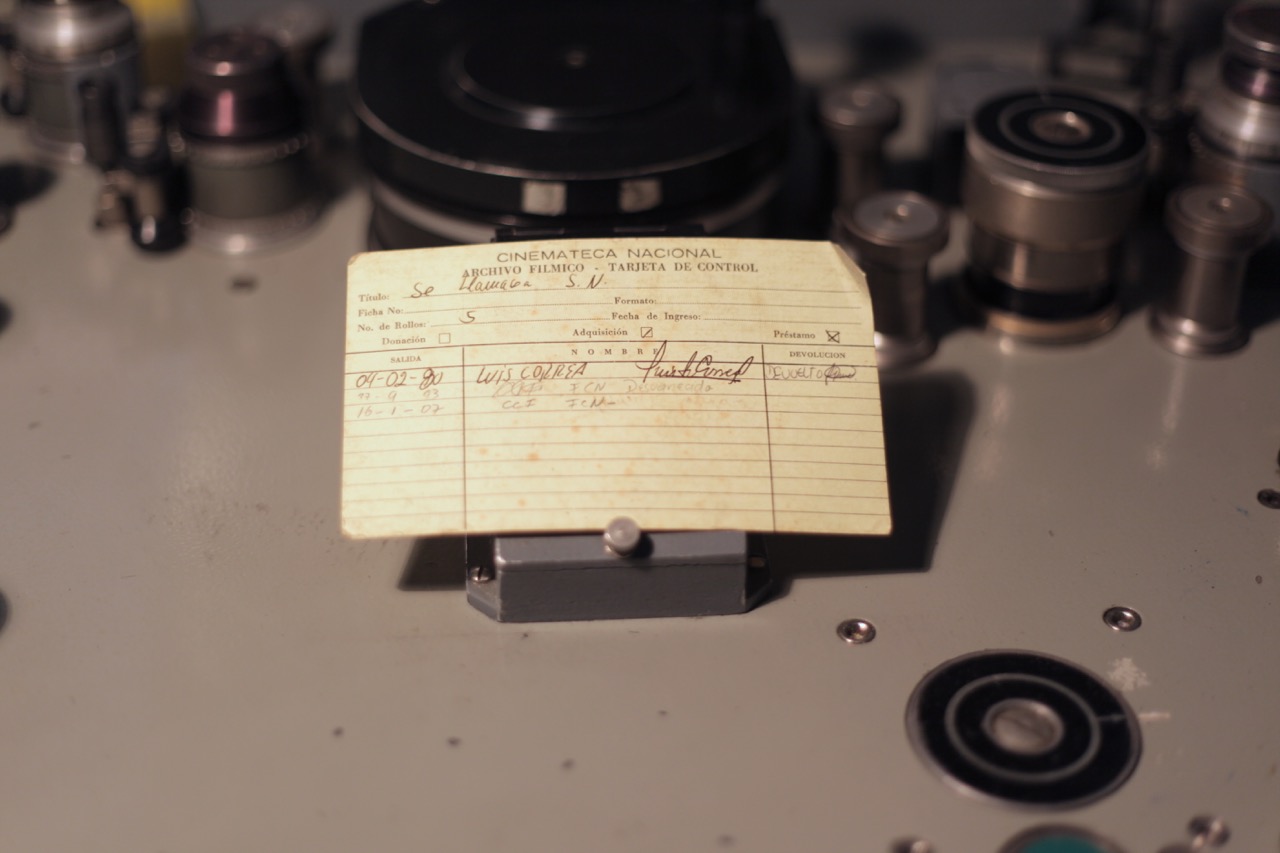

Archive record of the damaged film Se llamaba SN, Archivo Fílmico de Venezuela, 2013. Photo: Lisa Blackmore.

Teatro Agua y Luz, Feria de la Paz y Confraternidad del Mundo Libre, Santo Domingo, [1955], 2015. Still: Después de Trujillo, 2016.

Teatro Agua y Luz, Feria de la Paz y Confraternidad del Mundo Libre, Santo Domingo, [1955], 2015. Still: Después de Trujillo, 2016.

Monumento a los Héroes del 30 de Mayo, Malecón, Santo Domingo. Still: Después de Trujillo, 2016.

Carlos Figueroa e Iván Fernández, caretakers of the Casa de Caoba, Trujillo’s sacked mansion. Still: Después de Trujillo, 2016.