Celeste Olalquiaga & Lisa Blackmore, eds, Downward Spiral: El Helicoide’s Descent from Mall to Prison. New York: Urban Research, 2018

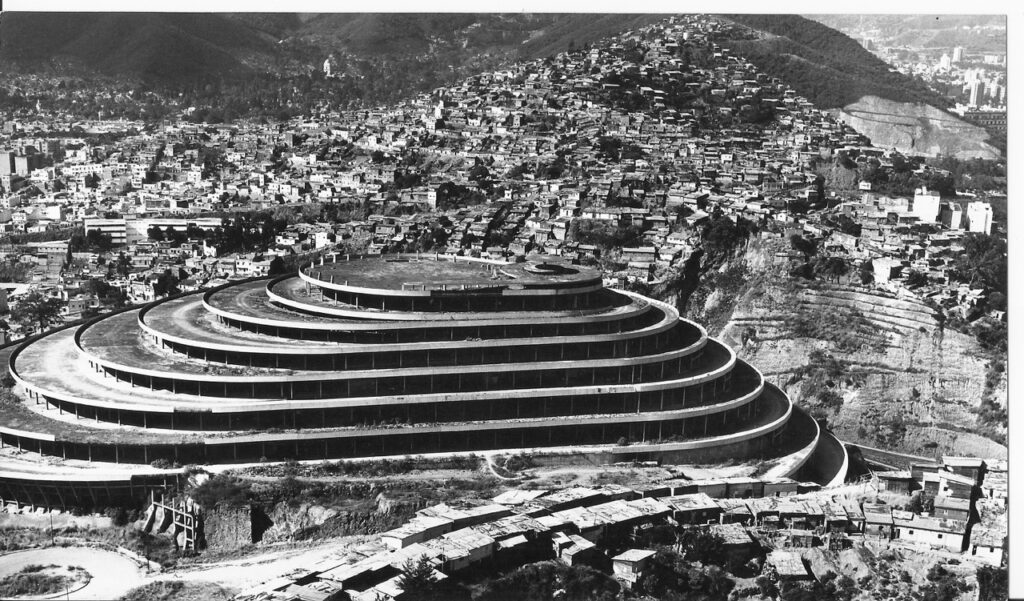

Hailed in the 1950s as a beacon of Latin America’s modernist architecture, Venezuela’s El Helicoide is a futuristic fantasy gone sour. At its conception, this drive-through shopping center embodied a narrative of progress, fueled by soaring oil prices, consumerism, and car culture. Yet a very different story unfolded on its spiral ramps. Caught in the transition from military dictatorship to democratic rule, El Helicoide became a site of abandonment, encircled by slums, and repurposed in1979 as an emergency shelter for flood victims. Since1985, it has been a headquarters for national intelligence and security police agencies, and an infamous prison. Combining archival documents, critical analysis, literary texts, and visual commentary, Downward Spiral traces the turbulent history of this living ruin and reveals the dystopic side of urban modernity.

Contributors: Pedro Alonso, Carola Barrios, Ángela Bonadies, Bonadies & Olavarría, Rodrigo Blanco Calderón, René Davids, Liliana De Simone, Luis Duno-Gottberg, Diego Larrique, Vicente Lecuna, Engel Leonardo, Albinson Linares, Sandra Pinardi, Iris Rosas, Alberto Sato, Elisa Silva, Federico Vegas, Jorge Villota. Designed by Álvaro Sotillo and Gabriella Fontanillas (VACA).

Celeste Olalquiaga & Lisa Blackmore, Introduction

El Helicoide de la Roca Tarpeya is more than an amazing building: it is a cultural phenomenon that represents the complexities and irregularities of urban modernity and, in Venezuela’s case, of democracy as well. Built as a futuristic beacon of private capitalist development and consumption in the late1950s, El Helicoide’s peculiar shape and monumental volume generated great admiration in the United States and Europe, contributing to Caracas’ growing reputation as a modern Latin American capital. Yet the project faltered mere months from completion and the building’s unfinished concrete ramps were relegated to the backdrop of the city’s slum-covered hills. Despite myriad private and public attempts at recovery,El Helicoide has only known two uses: first, as a temporary refuge for almost ten thousand people in the late1970s, then as a police headquarters and penal institution from1985on. This book, the first to address El Helicoide’s extraordinary architecture and history, seeks to rescue this singular site from oblivion. Doing so is also a way of recovering the collective memory of Caracas, where fast-paced change tends to overlook urban feats and letdowns alike.The city’s modernist heritage, now mostly demolished or degraded, deserves to be protected and studied. It bears witness not only to one of the most outstanding periods in Venezuela’s architectural history, but also to the social and political upheavals that modernity has entailed.

Lisa Blackmore, Out of the Ashes: Building and Rebuilding the Nation

In Venezuela’s urban history, stranded monuments are forgotten along with any lessons they might offer, as the gaze fixates instead on the next auspicious vision of the future, molded in new and purportedly definitive forms. Yet, in the shadows cast by gleaming monuments, the rubble at the intersection of nation building and architecture has its own story to tell. The geneses and afterlives of symbolic sites like El Helicoide can counteract this will to oblivion, recomposing a picture of the nation’s making to shine a light on past conflicts and present struggles. This chapter unearths and analyzes key exercises of monumental architecture and nation building, from the 1820s through to the late twentieth century, probing the dreams that undergird key symbolic structures.

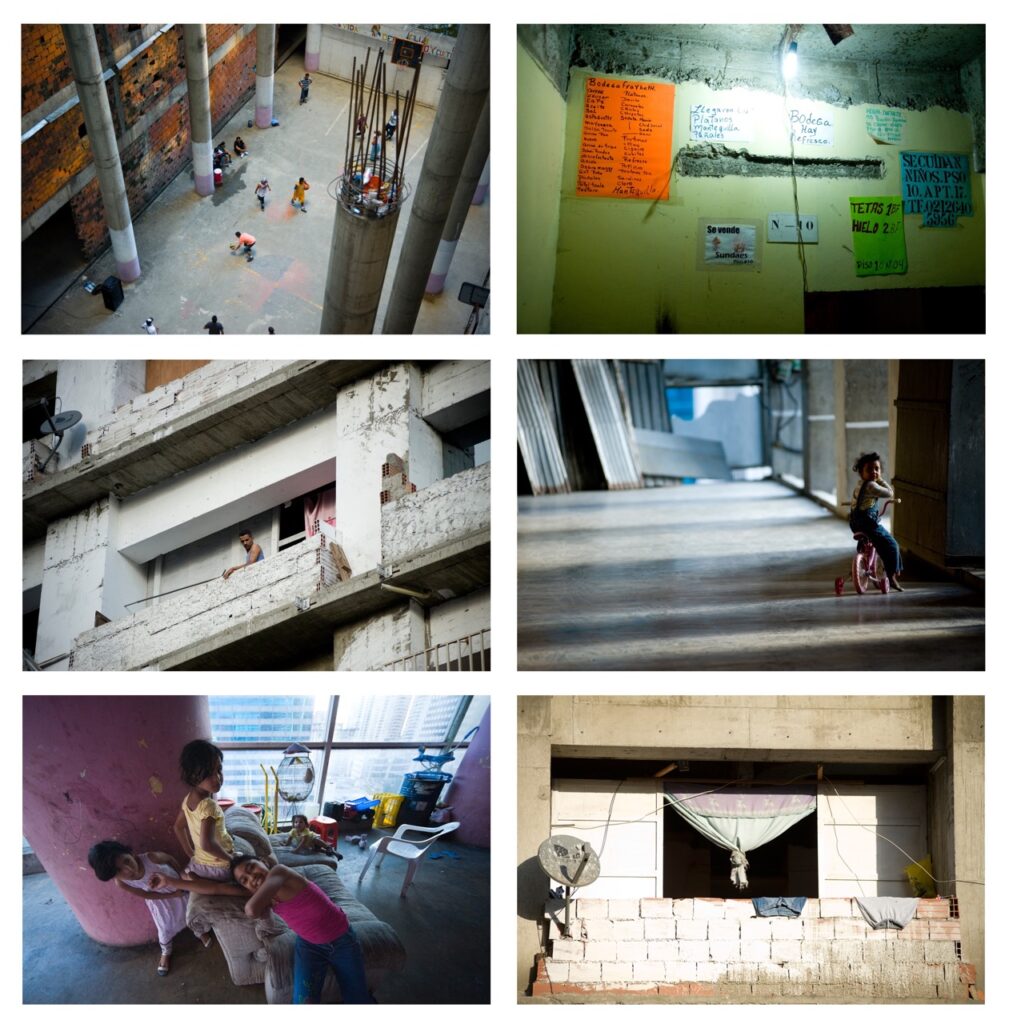

Lisa Blackmore, Makeshift Modernity: Container Homes and Slumscrapers

This chapter places in dialogue stories of informal occupation of two monumental urban icons in Caracas – El Helicoide in the 1970s and La Torre de David in the early 2000s. Despite the decades that separate them, retracing El Helicoide and La Torre de David’s respective descents into informal settlements unearths cracks that run deep in Venezuela’s national identity, its quest for “spectacular modernity,” and the upheavals that punctuate its political and economic development. Through their transient occupations, these buildings tell much more complex stories than those envisaged in their original grand designs. As figureheads of capitalist expansion through industry, consumerism, and speculative finance, El Helicoide and La Torre de David projected images of urban modernity that buttressed Venezuela’s “exceptional” status as a prosperous, albeit developing, nation. The grand scale of their architecture was conceived to overshadow precisely the marginal communities and precarious dwellings that might undercut the national vision of progress. However, these buildings’ transformation into makeshift housing opened them to the same vulnerable groups and provisional constructions that tend to be excluded by formal systems of spatial design and economic development. Part monumental contour, part improvised shelter, El Helicoide and La Torre de David became unintentional symbols of makeshift modernity: a complex reality shaped by a range of factors, from architectural hubris and economic volatility through to climatic catastrophes and political capriciousness.